Can Strategy exist without the Slides?

"You campaign in poetry; you govern in prose”

Mario Cuomo (attrib.) former New York Governor

When I joined Wieden+Kennedy Amsterdam as Chief Strategy Officer some 17 years ago, my eyes were truly opened to what a “deck” could look like. A level of craft, inventiveness, and care I had never seen before dripped from every slide. I looked back on my bulletpoint-infested presentations of old with shame. And for the next 14 years, I sweated every slide and every pixel, and beamed with pride at the gorgeous artefacts that my strategic department delivered day in and day out.

But it's good to unlearn some things, and I have begun to conclude that somewhere along the way, strategy became confused with presentation. Not explanation or articulation, but performance. The strategy “deck” - long, sequenced, meticulously designed - has become the dominant artefact through which strategic thinking is shared, judged, and legitimised. And yet, for something meant to guide decision-making under uncertainty, it feels strikingly ill-suited to the task it is supposed to perform.

The modern “deck” is designed to control a room, even to hold debate and challenge at bay. Its logic is linear and performative: it moves forward slide by slide, carefully (usually/sometimes) revealing insight, tension, and resolution. It assumes an audience that listens, absorbs, and eventually agrees. Oh please, we silently pray to ourselves as we plug in our laptops, do let them agree. But strategy does not exist to simply be absorbed. It exists to be used - argued with, stress-tested, and applied in situations far messier than the meeting in which it is first presented.

There are also cognitive problems at the heart of the “deck”. Even restrained slides tend to carry multiple signals at once: headlines, charts, metaphors, quotes, imagery, footnotes. The audience is asked to read, listen, interpret visuals, and follow an argument simultaneously. Coupled with that, is the fact that nothing is so effective as Slideware for exploiting the fact that we can only ever see one slide at a time, and thus disguising a lack of strategic logic and narrative coherence.

Length, too, is often mistaken for rigour. A hundred-page “deck” signals effort, diligence, and seriousness on the part of its authors. But production and volume is not the same as thinking. The hardest work in strategy is reduction: deciding what truly matters, what does not, and where we are willing to draw lines. Brevity is not a shortcut; it is the cost of having done the hard yards. And we know this.

Could it be that the theater and drama of persuasion satisfies something in ourselves? In his book The Win Without Pitching Manifesto, Blair Enns writes: “We will break free of our addiction to the big reveal and the adrenaline rush that comes from putting ourselves in the win-or-lose situation of the presentation. When we pitch, we are in part satisfying our craving for this adrenaline rush, and we understand that until we break ourselves of this addiction we will never be free of the pitch. Presentation, like pitch, is a word that we will leave behind as we seek conversation and collaboration in their place.”

At this point it is worth surfacing a more uncomfortable truth. The fetishisation of the deck is not accidental. It is tied to how agencies understand themselves. Many agencies are deeply invested in an identity as “creative” organisations, and the deck becomes a proxy for that identity. If the strategic work does not look impressive, if it is not visually rich or stylistically confident, it can feel like a threat - not just to the work, but to the agency’s carefully nurtured reputation. And so the “deck” persists, not because it is the best vessel for strategic thinking, but because it reassures agencies that they are still being who they believe themselves to be.

I have firsthand experience of the Amazon way of doing things. In 2004 Jeff Bezos had banned Powerpoint inside Amazon, and replaced them with 4-page memos (later expanded to 6-page memos). In an email to staff, he explained why: “The reason writing a good 4 page memo is harder than “writing” a 20 page powerpoint is because the narrative structure of a good memo forces better thought and better understanding of what’s more important than what, and how things are related. Powerpoint-style presentations somehow give permission to gloss over ideas, flatten out any sense of relative importance, and ignore the interconnectedness of ideas.”

No 90-page PowerPoint presentations full of painstakingly sourced high-res visuals, but a Word document instead. One that meeting participants were required to read for 30 minutes, in silence. As Jeff Bezos put it in an interview: “The reason we do this is that people often don't have time to read the memos in advance. They come to the meeting having only skimmed the memo or not read it at all, trying to catch up and bluffing like in college. It's better to carve out time for people to read.”

The excruciating awkwardness I felt sitting in meetings where everybody was required to read the document in silence notwithstanding, I increasingly come to the conclusion that there was some method in what at the time felt like some kind of psychopathic torture test. It slowed things down. It forced attention onto the thinking itself, rather than onto how convincingly it was being delivered.

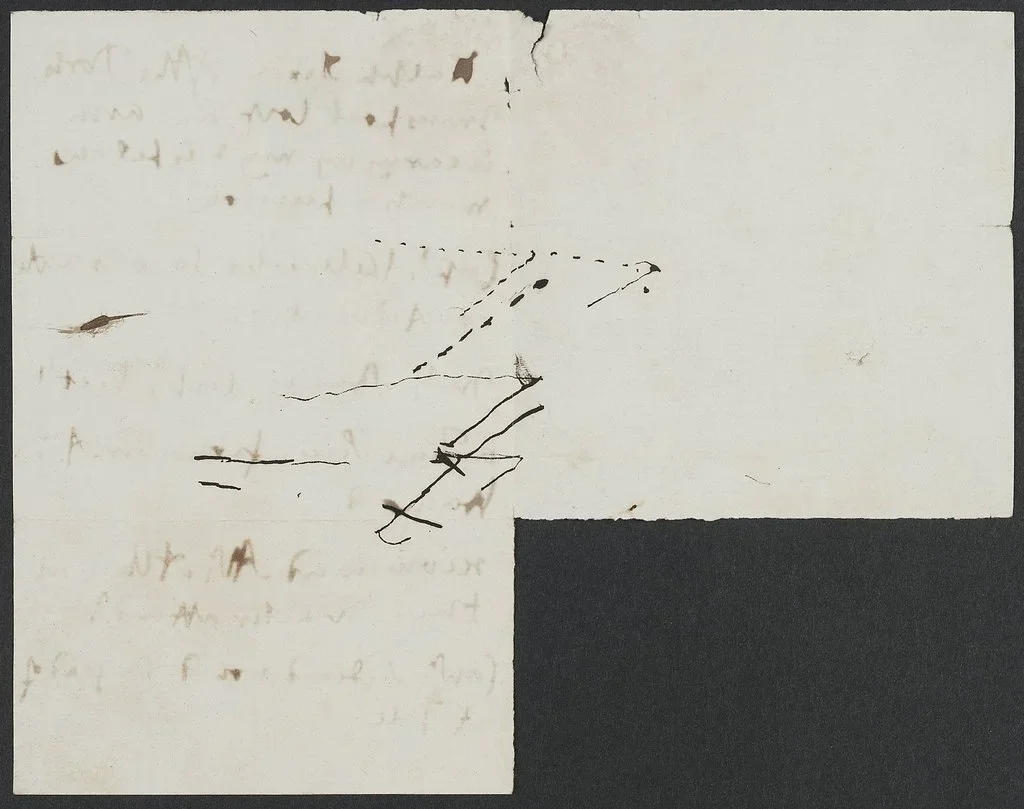

Strategists are fond of opining that “strategy is sacrifice”. Reduction, distillation, judgement, choice, and focus - this we know, is the essence of strategy. Pressed for time, Admiral Nelson distilled his concept for how victory would be achieved in what became known as the Battle of Trafalgar in just a few words: "No day can be long enough to arrange a couple of Fleets and fight a decisive Battle according to the old system… With the remaining part of the Fleet formed in two Lines I shall go at them at once… I think it will surprise and confound the Enemy. They won’t know what I am about. It will bring forward a pell-mell battle and that is what I want.” He accompanied them with a hastily drawn sketch:

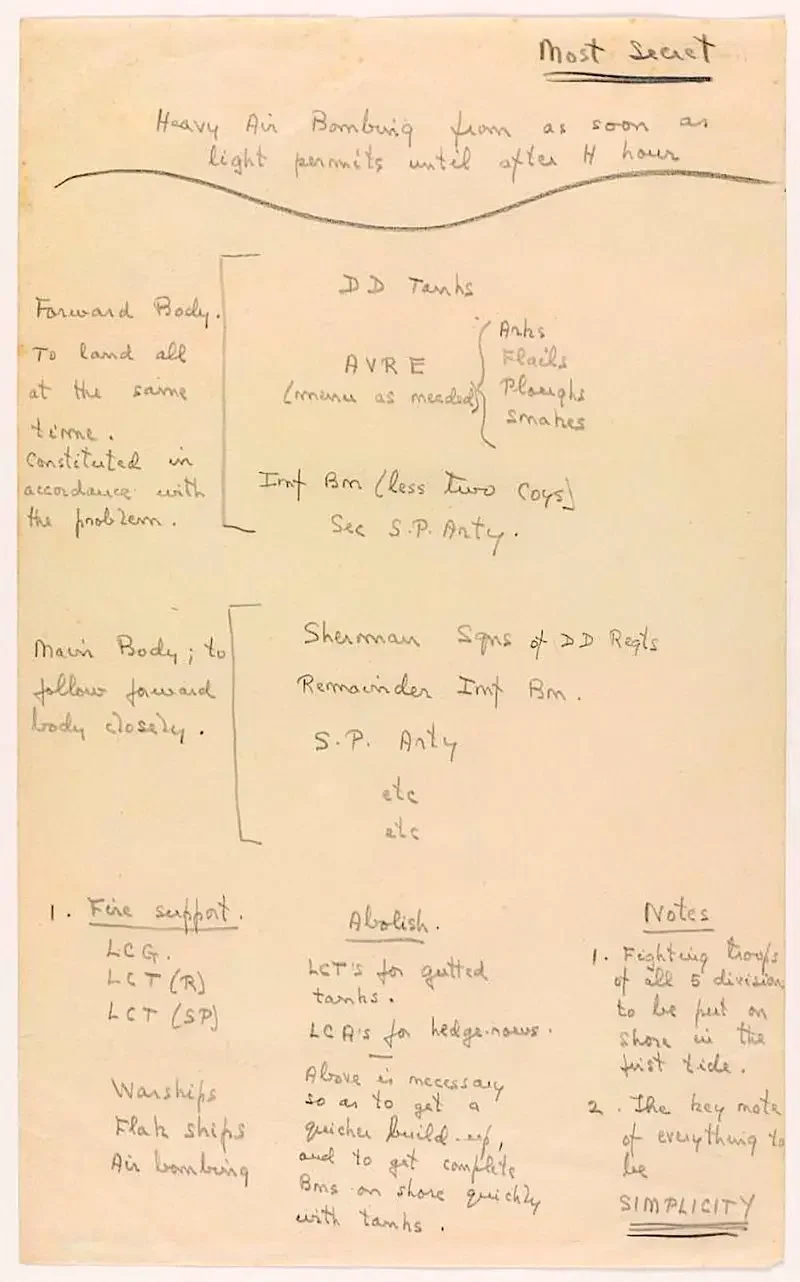

While the full Overlord plan itself was of course vastly more detailed, Montgomery managed to distill his D-Day concept into a single-page handwritten outline that captured the logic and priorities:

We know that brevity in strategy is not performative minimalism. So why the industrial scale slide-count? Could it be that we feel compelled to make our case at painstakingly and gorgeously art-directed length because we worry (or know) that our audience just don't trust us or believe us that much? One has to wonder.

I delivered a brand strategy for a client the other week that represents a major evolution for both how they think about themselves, and what they will invest in over the long-term. It took up less than one side of A4, and took less than 5 minutes read - leaving the other 85 minutes of the meeting for discussion, challenge, and optimisation. It can be done. Perhaps it helps to remember that for decades great brands (that still feature prominently in our everyday lives) were built without the aids and tools we feel we cannot live or succeed without.

That said, not every forum is a decision-making forum. There are times when the task is not judgement but persuasion - when the objective is to galvanise employees, reassure partners, or enrol a broader set of stakeholders behind a direction already chosen. In those contexts, theatre can absolutely play a legitimate and indeed vital role. In these moments, a “deck” may be useful in creating shared energy and momentum. The mistake is not using those artefacts at all, but using them indiscriminately - and allowing tools designed for mobilisation to masquerade as tools for strategic thinking and decision making.

Personally, I am finding that it helps to think about what kind of meeting or forum I will be finding myself in. To my mind, in the doing of strategy there are three very different kinds of meetings, calling for three very different kinds of inputs:

Consultative meetings - to which one brings one’s ears

Strategic work and alignment meetings - to which one brings provocation, options, and a decision-making framework

Enrolment and belief meetings - to which one brings drama and persuasion

Only one of these might require the widescreen, Technicolour, all-singing, all-dancing “deck” that we cling to.

Just a thought.

By the way, Jeff would be proud. This post fits on 2.5 sides of A4.

***

Want exciting strategy, but without the dramatics and the 90-page deck?

Let's talk:

martin@emdub.co

Martin Weigel is a brand strategist, former Chief Strategy Officer at Wieden+Kennedy Amsterdam, and founder of EMDUB. He helps companies find their superpower - and turn it into action.